The oil watcher Robert Mabro, who died last month, once quipped that OPEC should change its logo to a tea bag “because it only works when in hot water.”

In light of recent events, that’s turned out to be quite the prescient observation.

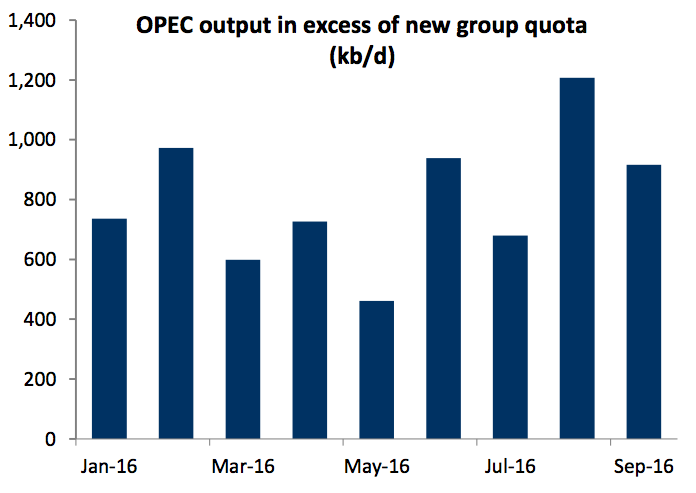

On Wednesday, the oil cartel reached an agreement at informal talks in Algeria to limit its production at its November policy meeting to a range of 32.5 million to 33 million barrels a day, down from today’s estimated level of 33.24 million barrels a day.

Prices for Brent crude oil, the international benchmark, surged by over 6% in the immediate aftermath, touching what was more than a two-week high of $48.96 a barrel. US energy stocks followed suit, as did petrocurrencies such as the Russian ruble.

Most analysts hadn’t gotten their hopes up ahead of the latest talks in the Algerian capital, Algiers, arguing that geopolitical tensions and strategic market interests would translate into another wash the way they did at the cartel’s meeting in Doha, Qatar, back in April.

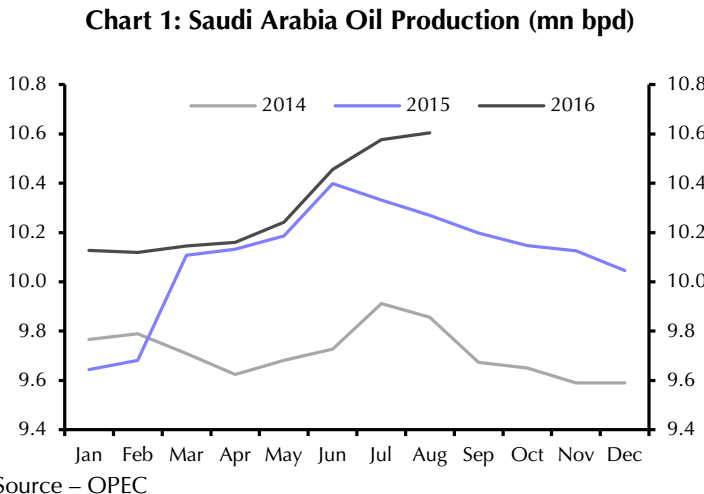

So the decision to limit production appears to be a "major turnaround" for Saudi Arabia and reflects the kingdom's growing economic stresses at home, according to Helima Croft, the global head of commodity strategy at RBC Capital Markets.

"[We] believe it was key domestic considerations that caused the Kingdom to put aside its regional rivalry with Iran and pursue pragmatism," Croft wrote in a note to clients on Thursday.

She continued: "We also believe that Saudi Arabia will be pretty determined to make the deal stick as it has so much on the line and put so much diplomatic effort behind forging the consensus in Algiers."

The kingdom announced several fiscal-consolidation measures this week, including cutting ministers' salaries by 20% and canceling bonus payments for state employees, in an effort to reduce its record budget deficit. And that's notable given both that two-thirds of working Saudis are employed by the state (so consumption will take a hit, and the wage cut could increase political risk) and that the kingdom's earlier cuts on electricity and water subsidies were not well received by the public.

Plus, the kingdom's foreign-exchange reserves are down almost $190 billion since oil prices started falling, Bloomberg reported earlier that the country was aiming to cancel over $20 billion worth of projects and to slash ministry budgets by one-quarter, and there have been several ugly economic data points.

"While talk is cheap and execution is paramount, the reinstalling of a group quota system is a constructive outcome given that the lack of a quantifiable measure of accountability has proved elusive and plagued OPEC over recent years," Croft's team added.

Nevertheless, for all the post-announcement hoopla, there remain key unanswered details. Chief among them, as an HSBC team led by Gordon Gray, the global head of oil and gas equity research, outlined:

- It's unclear how the production cut will be divided up among the members. The duration of the production limit. How the limit will be enforced and overseen. Whether Nigeria and Libya, where production has plunged over the year amid domestic-security issues, will be subject to cuts. Whether Iran, which is keen to keep production up post-sanctions (and has repeatedly expressed that it does not want to cut), will also be subject to the production limit. And finally, whether non-OPEC members (read: Russia) will participate.

Diving into the actual numbers, a Citi Research team led by Edward L. Morse noted that "Saudi Arabia might be reducing crude output by as much as 0.5 million barrels per day going into 4Q'16 in any case, as internal crude oil demand for power generation goes down seasonally after the summer peak; much of this cut is what would have happened regardless of any deal."

"Look deeper and the 'deal' becomes less and less meaningful, and more and more rhetorical," his team added.

On the geopolitical front, a BMI Research team argued that given the ongoing regional tensions, "any concessions by Saudi Arabia or Iran will hinge on the promise of strong fiscal returns."

In other words, they will want to see a significant - and, crucially, sustained - hike in energy prices.

"For this reason, we question the rationale for a cut," they argued. "Resilience in US shale output has consistently surpassed expectations, while output gains in Russia continue to accelerate. OPEC has indicated that it will reach out for cooperation from key non-OPEC suppliers, although we believe this cooperation is unlikely to be forthcoming from Russia."

As a final note, it's worth pointing out that coordinated action between the cartel's members doesn't necessarily have to be long term. Or as a Macquarie Research team led by Vikas Dwivedi put it several weeks ahead of the meeting in Algiers:

"Even if a 'freeze' truly materializes, it will provide little fundamental impact. From a longer-term perspective, core OPEC and non-OPEC producers are eyeing $50+ levels to enable future growth. [...] Thus, instead of a meaningful rapprochement among key producers, a 'freeze' may merely represent an opportunity to 'reload' only to resume oil market hostilities."

In short, everyone will be watching what OPEC will do at its November meeting in Vienna.

And given that the markets have grown somewhat skeptical of the cartel's chatter, they will probably going to want to see some action.